Der Fotograf Henry Chalfant, Autor des Klassikers SUBWAY ART, hat der BBC ein ausführliches Interview gegeben, in dem er sechs seiner persönlichen New York City Wholecar und End2End Highlights aus den Jahren 1977 bis 1981 zeigt und auch erklärt warum. Mit dabei auch unser Highlight, der Style Wars Wholecar von NOC167 aus dem Jahr 1981. Sehr interessanter Artikel (englisch)!

Trainspotting: Shooting the graffiti art of New York’s subway cars

I grew up in Sewickley Heights PA, an affluent suburb of Pittsburgh where steel executives had country estates. We lived on a “gentleman farm”, with 16 cows, some sheep, chickens, pigs.

My freedom was virtually unlimited, until it was curtailed by my parents’ insistence on adhering to the social obligations of the golf club life and boarding school, against which I chafed and which bore the seeds of my alienation.

My adolescent rebellion, foreshadowing my interest in graffiti, was expressed through cars, motors, and speed.

I created my first “hot rod” from an old Ford: souped up the motor, repaired the rusted fenders, attached dual exhausts with steel pack mufflers which made music in my ears but shattered the peace of everyone else.

After three years at university, I missed working in the physical world, and the pleasure I had gotten from working with my hands on my old car, and I felt inspired to take up sculpture. I learned to carve wood from a Catalan sculptor in Barcelona.

My wife, Kathleen, our two children and I moved to New York where I set up a sculpture studio and she began her acting career.

In 1973, graffiti had already evolved within two or three years from simple tags to elaborate calligraphic works covering the entire sides of subway cars.

I was enthralled and enjoying the spectacle of freshly painted cars rolling into the station on my morning commute to the studio.

It wasn’t until four years later when, unable to resist any longer, I found my way to the elevated 2 and 5 line in the Bronx to begin to take the pictures that make up my collection.

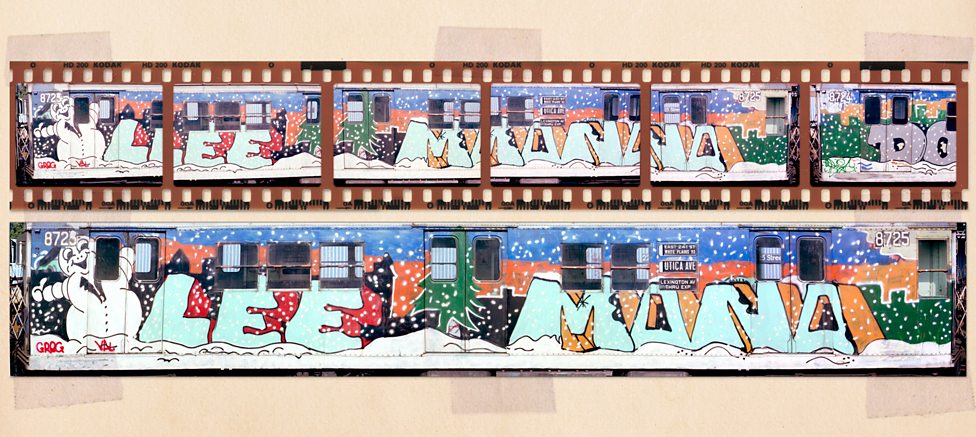

Lee Mono Doc “Merry Christmas” train, 1977, by Lee. © Henry Chalfant.

This was the first photo-montage of a graffiti piece that I did and the one that set me on the course to document subway art using this method.

It was the summer of 1977, and I had decided to find a way to take pictures of graffiti on New York’s subways.

One day as I rode up to the Bronx on the 2 train, between the Prospect Avenue station and Intervale Avenue, there was a train parked in the center track, between the uptown and downtown tracks.

I saw the Lee Mono Doc “Merry Christmas” train parked there, and wanted very badly to photograph it.

In order to do that I would have to run out on the catwalk between the two stations, to get to a position beside the parked train. I knew I had to get out there and back before another uptown train came through which would have been dangerous and frightening, as the catwalk was very narrow.

I ran out, and took about 10 contiguous photos until I had covered the length of the two cars, then I ran back and climbed up on the station, to the disapproving glares of the other passengers.

Once the photos were developed, I spliced them together in my studio and pasted them in an album, the first of more than 800 painted subway cars that I would collect before I stopped about seven years later.

Stop the Bomb train graffiti, 1979 by Lee © Henry Chalfant.

This work of art is painted on two subway cars permanently attached, called “a married couple” by the writers.

Lee painted it by himself in a location known only to him in 1979, when the anti-nuclear movement was still growing in strength toward its peak – the massive demonstration that took place in Central Park in 1982.

When graffiti was evolving into a fully developed mural art, many of us observers thought that it would become a new voice for the oppressed to bring attention to issues and to and create a community of people who could use the medium to make social change.

I remember in the early years trying to encourage people to make political art, thinking that this was a wonderful opportunity to stand on a soapbox and be heard. But except in a few instances, this would never happen.

The central element of graffiti continued to be getting your name up. It was this attribute of graffiti that was so popular and that made it spread so far and so fast till it became a world-wide phenomenon.

It seems that the idea of a marginalised people finding a way to put up their name and by extension their identity for all to see, was the very element that made the practice so popular.

It was not so much to “say” something that would influence the course of events in the world, rather it was the growing accumulation of millions of individuals showing their name that had the most impact.

Much like the pop-philosopher Marshall McLuhan once announced, “… the medium is the message”.

So Lee’s works that contain political and social content are very rare and they foreshadow a kind of expression that would appear much later in the Street Art movement.

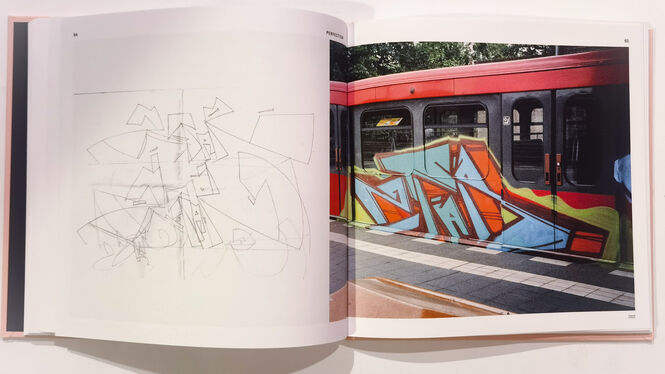

Kel Futura, 1980 by Kel 1st and Futura 2000. © Henry Chalfant.

Another favorite of my favorites is the Kel Futura car, because Kel 1st painted characters originated by the underground comic artist, Vaughn Bodē.

These characters were ubiquitous on subway cars in the 1970s. Vaughn Bodē, an artist and comic book creator whose style was rooted in sixties psychedelia, had a tremendous impact on graffiti artists.

Writers from the mid-seventies on drew upon Bodē’s imagery, painting thousands of his lizard characters on the trains.

The lizards spoke street slang with Brooklyn accents and they made ideal outlaw role models for young adolescents forging a new persona for the streets. Painting one of these characters on the train was as much a projection of self as painting your name.

Hand of Doom, 1980 by Seen UA. © Henry Chalfant.

Subway art, being vulnerable to the elements and especially to the Transit Authority’s chemical car wash, was an ephemeral art in New York City.

Not only the car wash, but rival crews with a grudge, or in competition for painting surfaces, who would cross out your piece, threatened every work of art.

This was a source of anxiety for me, since it meant that I had a very short time to photograph any new piece before it was destroyed.

So imagine my excitement when I was lucky enough to be at the right place at the right time to see a freshly painted whole car, such as The Hand of Doom by Seen UA, and to be able to photograph it, even before the workers had scraped the windows clean, which they usually did at the first opportunity.

If photographing subway graffiti is like big game hunting (it is!), I had bagged a tiger.

Ever since the news media became aware of hip hop in the late seventies, they included graffiti as one of the four elements of hip hop; rapping, DJ-ing, rocking, and graffiti. This categorisation is not quite accurate.

Graffiti writing predates the emergence of hip hop and the other three elements by several years. In fact there were many writers who came from a culturally different background who did not think of themselves as be part of the culture of hip hop.

Seen, for instance, was of Italian American descent and grew up in the East Bronx, a predominantly Italian neighborhood. He and his local crew of boys growing up listened to very different music than most of the black and Latino kids in other parts of the city.

The Hand of Doom is inspired by a Black Sabbath album. Older Latino writers were listening to salsa or Latin rock, like Santana.

So for me, The Hand of Doom represents diversity. The original graffiti scene in New York was multicultural. There were wonderful black artists like Chain 3, Asian artists like Mackey, Caucasians like Zephyr and Latinos like Kel 1st.

The diversity I found, when I began to get to know the writers, broke down all the stereotypes I had held before about who was writing graffiti in those days.

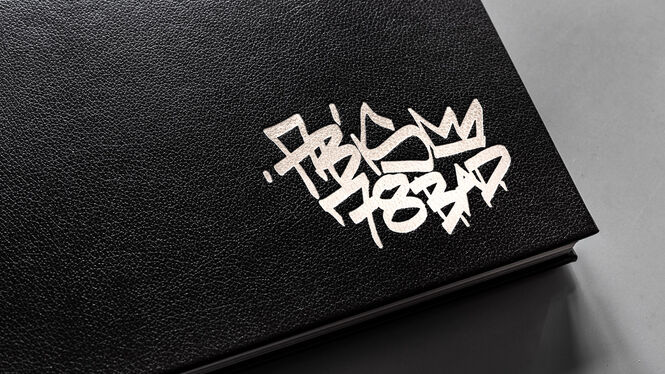

Style Wars, 1981 by NOC167, © Henry Chalfant.

NOC 167 was a Bronx writer and a member of one of the greatest uptown crews, TDS – The Death Squad.

TDS was one of the most influential crews, producing a calligraphic style of writing that would become known as Wildstyle, the energetic interlocking letter forms that were the model of graffiti that writers in New York would use for years to come, and that writers around the world would imitate as the model of authentic graffiti.

In the winter of 1980-81, NOC 167 created this mural on one of the West Side IRT trains. He spent 12 hours painting it by himself.

When I first saw the car, I was amazed, it was a richly conceived and executed work of art, filled with imagery, both realistic and fantastic, that combined trains, track, signal towers and comic characters borrowed from Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards.

In keeping with the title, the two words were written in both Wild Style and Straight letters. The name has multiple meanings, starting with a war of lettering styles, it also refers to the battle for hegemony over public surfaces between the city authorities and the graffiti writers.

This in turn opened up an even greater philosophical conflict over public ownership – who has the right and privilege to decide what the public will see every day?

In this way, graffiti writers challenge something that our mercantile society holds as sacred, the right of people and corporations to use the public space for selling their goods. How much say does the public have over that visual environment?

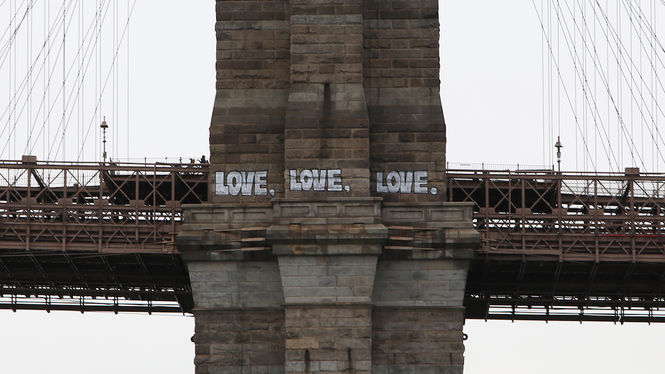

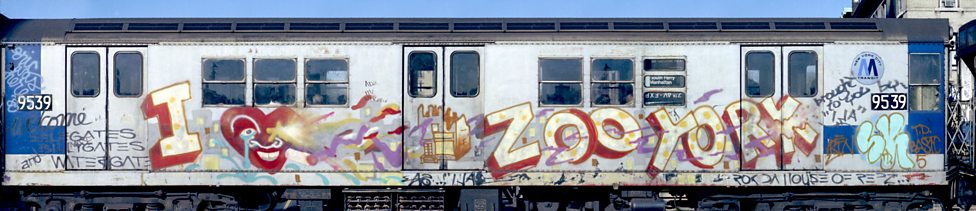

I Love Zoo York, 1981 by Ali. © Henry Chalfant.

The I Love Zoo York car, which ran on the 2 and 3 line, was painted in 1981 by an old school graffiti writer named Marc Edmonds, whose tag was ALI.

Marc had formed the writing crew, Soul Artists, in the early seventies. Graffiti writers had coined the name Zoo York from a train tunnel that ran under the Central Park Zoo where they often went to paint.

Zoo York is a wonderfully apt, ironic play on the name for New York City, which was in serious decline in the decade of the seventies.

By 1979, there were signs that graffiti was beginning to catch the attention of the media and the art world, and Marc was prescient enough to see that there was a growing potential for the creation of a real art movement.

He brought Soul Artists back to life, and began to hold meetings in his neighborhood storefront, with graffiti writers, which I was lucky enough to attend.

Marc’s idea was that, as the movement grew, the directors of galleries and museums would want to get into the action and he saw that it was important that the artists themselves keep control of the production and the direction the movement might take.

The grass roots community Marc was trying to build ultimately didn’t hold up against the onslaught of money, media interest and the mainstream culture that wanted to create individual superstars.

The movement fragmented when individuals, who were singled out by art dealers, jumped at the chance to become professional artists, breaking the bonds of crew solidarity.

But Marc’s idea that these young artists could, in fact, have a career in art was an idea that endured and was fulfilled for many.

Quelle: BBC